So, I’ve finally finished up auditing all the puzzles in the game. Essentially, just solving them all and taking notes on what might need to be improved or removed. Overall, I think the game is in a pretty good place moving forward. There are some areas that I’m pretty happy with as is, but there is still a lot of work to be done to improve some other areas. Obviously this is just considering design work. Let’s not even get into how behind the curve I am from an aesthetic point of view.

Early Accessibility

This week, I chatted with a deaf accessibility advocate for games. This was an interesting and challenging conversation, and has left me thinking a little bit about what’s involved in making a game more accessible, and how that intersects with the design of Taiji. Obviously, I think that accessibility is an important and often ill-addressed concern, and my goal with the game is to never make a puzzle difficult for reasons that have nothing to do with its subject matter.

However, I think there is some tension between accessibility concerns and the pursuit of particular subject matter. As an example, if you want to do puzzles that are “about sound”, deaf people will unfortunately, but necessarily, be excluded.

It is easy to see why making a puzzle that relies on pure audio cues is a bad move from an accessibility standpoint. In many cases, it would be easy to make additional visual cues, and to not do so can simply be chalked up to laziness.

But my big question is, are there particular cases when not adding those cues can be justified? And if there are, what are they?

Some of my thoughts on this are a bit hard to clarify without specifically addressing and spoiling some of the puzzles planned for Taiji. Even still, after discussing the details of the puzzles with the aforementioned accessibility advocate, they did not seem particularly convinced that there was any tension other than my laziness and lack of care.

Similar concerns arose in the wake of the release of The Witness. There are some puzzles in that game which people who are color-blind or hard of hearing will have trouble with, or may simply find impossible without just looking up the solutions. Because of this, the designer—Jonathan Blow—has been called callous, “ableist”, or at best unconcerned about accessibility. The last one is particularly strange, considering the game received a PC patch to add a click-to-move mode, and nearly all of the puzzles in the game—including many that use color as a cue—are designed to be as accessible as possible; symmetry puzzles that care about colored hexagons using cyan and yellow, for example. In my last point of defense of Jon Blow before I move on, he has been quoted saying that he wanted to ship the game with a puzzle which only color-blind people would be able to solve, however in this case he was hamstrung by the the poor color consistency of most display technology.

So, what is the reason to make those kinds of decisions? To create puzzles which by their very nature exclude certain people from fully enjoying your game? Jon Blow says it is because the puzzles in The Witness are all “about things.” I agree with this sentiment, but it perhaps requires a bit more clarification to even make sense.

In many puzzle games, the “point” of the puzzles is essentially to be a challenge. The puzzles are meant to be hard for the player to solve, and probably fun as well. In games like The Witness (or Taiji, for that matter) the point of the puzzles is significantly subtler. The puzzles are intended to be interesting and, about something real. By “real” I mean that the subject matter is, at best, not confined simply to the game. The thinking that a player will do when solving the puzzles can be taken with them back into the real world.

It may seem a bit callous, but it should go without saying that both sound and color are phenomena that really exist, even if some people cannot experience them.

This can seem to lead down a path of reckless disregard for other people, so I think it is also very important to emphasize that what I’m talking about here—both in my own case and the case of The Witness—are puzzle games. These are games that, by design, will exclude people who are simply not intelligent enough to complete all of the puzzles in the game.

So What?

Perhaps all of this can just be seen as a long elaboration intended to serve as an excuse for my laziness, or “ableism”, or perhaps some other unidentified flaw of character. However, I still have not addressed the core issue:

What am I going to do about accessibility?

Currently the plan is to make the game as accessible as I can. When puzzles involve the use of color for separation, but are not explicitly about color, I will endeavor to choose colors that will work for as many people as possible for that purpose.

But what about when puzzles are explicitly about those things? What about puzzles about sound, for example?

In these cases, I will primarily design the puzzles with the intent of pursuing the subject matter that interests me. If I have to choose between a puzzle which can be made accessible or painting myself into an inaccessible but more interesting corner, I will most likely choose the corner.

However, I also intend to provide some level of assistance when possible. This, in itself is a tricky proposition, because I do not simply want to condescend to players who are using the assistance options. In essence, adding accessibility seems as though it will often amount to designing an entirely different set of puzzles. The puzzles therefore must be interesting in their own unique ways, and must endeavor to be analogous to, and at least as challenging as, the inaccessible puzzles.

Perhaps this will not be enough, or not even be possible. After all, I am mostly opining here without having fully designed any set of puzzles like this. But I think this is the best way for me to balance these two ideals: accessibility and truth.

Addendum

I want to clarify a couple things: What exactly is the difference between a puzzle which is about sound or color and one that simply uses it as a cue. And why do I think that the former cannot be made accessible without simply designing a different set of puzzles?

To do so will require spoiling a couple puzzles. The Witness is a hugely broad puzzle game, so I can actually find examples in both the positive and the negative without talking about any other game.

Spoiler Warning: If you have not completed the two areas shown below in The Witness, then avoid reading further.

The Keep

So, in the example of puzzles which simply use audio as a cue, but are not really about sound; we have the example from The Keep. The third hedge maze puzzle in the front courtyard must be entirely solved by listening to the loudness of your footsteps while walking on the gravel pavement inside it. The maze on the panel matches the shape of the hedge maze which contains it, and particularly crunchy spots found while walking through the physical maze denote an area to be avoided when drawing a corresponding path through the maze on the panel.

The reason that I say this is not a puzzle about sound, is that it would work just as well if you simply wrote out separate captions for the footstep sounds. The softer ones being written as “crunch“, and the louder ones being written as “CRUNCH“. The puzzle would essentially work the same.

It is important here to note the difference between subtitles and captions. Subtitles only show you spoken dialogue, whereas captions will also give you a textual indication of important audio cues.

The actual puzzle here is about noticing that the loudness of the footstep might be important, and then figuring out in what way. The argument against accessibility here is that hearing players are inundated with the sound of their footsteps throughout the whole game, and so this is a subtle thing to notice. Consequently, captions would be much less subtle.

I think this is actually not a very good argument: First, it isn’t really that subtle, as the important footstep sound is unusually loud here. And secondly, if the consistency is really that important, just put captions on all of the footstep sounds in the game. Make them small and unobtrusive if you have to.

Sadly, The Witness does not support captions at all, and therefore this puzzle is impossible for deaf players without simply looking it up.

The Jungle

So, in the positive example, we have the puzzles in the Jungle. These are puzzles that are actually about sound, or more specifically: about hearing. This will be harder to explain, because the puzzles themselves are much more subtle.

First, if you need a refresher on the content of these puzzles, I actually have an analysis video on the first half of this area, in which I discuss some of the subtle details involved:

Now, I want to bring the attention to my specific point earlier. Why do I think that these puzzles cannot be made accessible without simply making a different set of puzzles?

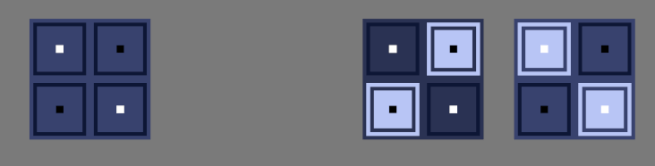

In this area, the essential task that the player is doing is listening to some bird songs, and transcribing the different pitches of the notes onto the panel. One could easily imagine some sort of analogous visual cue: a series of mechanical birds which all chirp in time with the notes, and are set on branches of varying height, with the height of the branch corresponding to the pitch of the note.

This type of cue would in fact work quite well, but only for the first three puzzles in the sequence. Past that point, the puzzles begin to play with both the particular difficulty of distinguishing different notes by ear, and the way in which we focus our attention on certain sounds by filtering out others. Both to our benefit and our detriment.

Perhaps again, there could be some analogous changes to our cues here. Perhaps the birds start out in linear order as they would be on the panel, but they begin to be shuffled up, and the player must watch the order in which they chirp. Perhaps the branches which the birds are situated on begin to blow in the breeze, and so it is more difficult to tell which bird is supposed to be higher. Perhaps there is a branch which is broken and the bird has fallen onto the ground. Perhaps there are birds which are not situated on branches at all, and they are irrelevant. These could be interesting ways to evolve the sequence, but what I am trying to argue is not that the puzzles cannot be made accessible, but that by doing so, they are now puzzles which are fundamentally about something different.

They are no longer puzzles about sound, and now are puzzles about spatial relationships between moving objects.

Does this make these accessible puzzles bad? No. But it does make them different puzzles.

Obviously, pacing in games is very important, but this comparison got me wondering about how exactly you pace games which focus on puzzle-solving. It’s not that I haven’t thought about this at a subconscious and abstract level. In designing Taiji, I care very deeply about making sure that the game is as interesting as possible, and this often means addressing pacing, at least in some hand-wavy way. But, I’ve mostly been playing by ear, and I haven’t put forth my approach as a formal set of design guidelines.

Obviously, pacing in games is very important, but this comparison got me wondering about how exactly you pace games which focus on puzzle-solving. It’s not that I haven’t thought about this at a subconscious and abstract level. In designing Taiji, I care very deeply about making sure that the game is as interesting as possible, and this often means addressing pacing, at least in some hand-wavy way. But, I’ve mostly been playing by ear, and I haven’t put forth my approach as a formal set of design guidelines.